Metropolitan Playhouse

The American Legacy

The American Legacy

"Theatrical

archaeologist extraordinaire" - - Back Stage

|

Metropolitan Playhouse

The American Legacy "Theatrical

archaeologist extraordinaire" - - Back Stage

|

|

|||||||

| Playing | Next | Season | Tickets | Company | Location | Mission | History | Links |

|

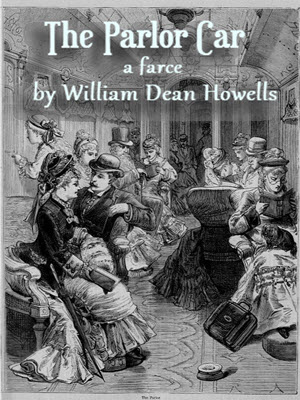

| The

PARLOR CAR Farce |

|

|

|

|

“You must tell me,

dearest, what I have done to offend you. The

worst criminals are not condemned unheard. And

now I only ask you to be just.”

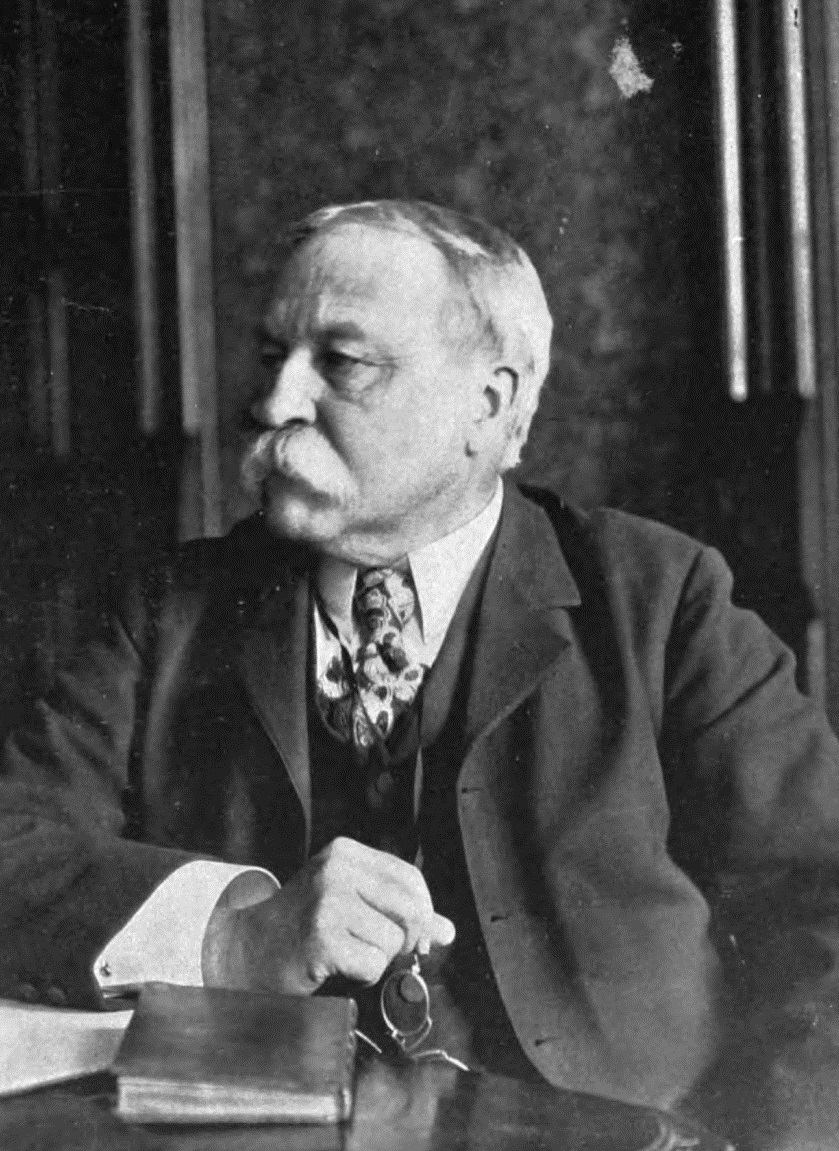

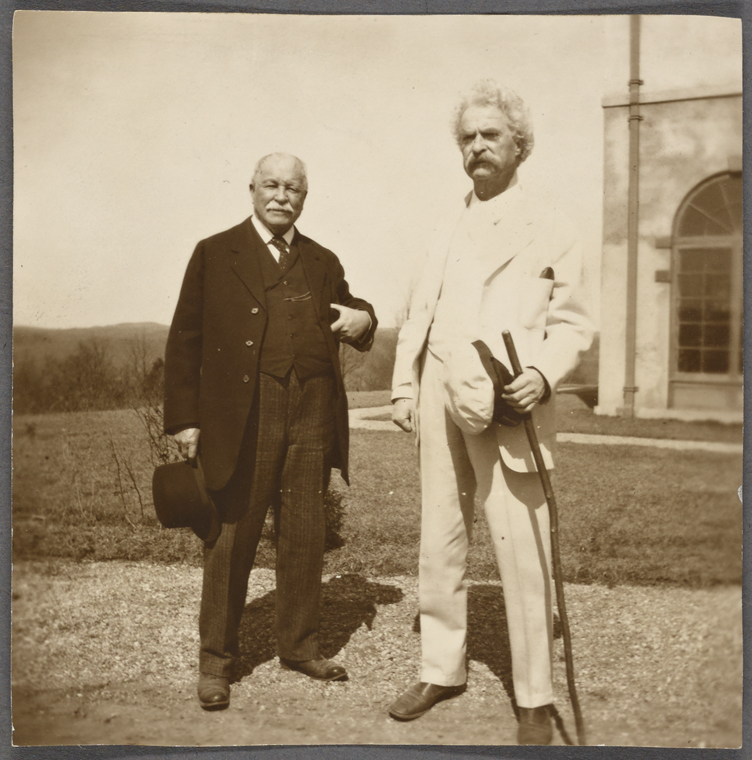

“You know very well what you’ve done. You can’t expect me to humiliate myself by putting your offence into words.” “Upon my soul, I don’t know what you mean! I don’t know what I’ve done. ”  William Dean Howells and Drama as Literature William Dean Howells (1837-1920), American writer and editor, was an influential critic and an important novelist of the late 19th century. His career spanned a period of radical change from European influenced conventions in American literature to Realism; as novelist, critic, and editor, he contributed greatly to those changes. His novels appeared almost every year from 1987 to 1921, he managed to write six autobiographical studies, more than a dozen travel books, four volumes of poetry, numerous memoirs, biographies and reviews. And 30 plays. He was not known for these dramatic efforts, which were far more literary than stage-worthy. Rather than receiving professional productions, these one-acts plays were published regularly for review in literary digests, principally The Atlantic Monthly and Harper's. His plays were described as 'closet dramas' for reading and not necessarily performing and he was meticulous in crafting his stage directions as he was in his dialogue. He enjoyed exploring realism in the dramatic form, as with his novels, to tell the truth of the everyday lives of Americans. He had no interest or talent for the role of Actor/Manager, the only way a playwright could earn a living in early 19th century American theatre. His first published play was, in fact, The Parlor Car published in The Atlantic Monthly, August, 1876. (See the illustration above right.) after he had already written three novels, a book of poems and numerous articles and essays. Realism in American Plays Melodrama The drama of the pre-war period tended to be a derivative in form, imitating European melodramas and romantic tragedies, but native in content, appealing to popular nationalism by dramatizing current events and portraying American heroism. But playwrights were limited by a set of factors, including the need for plays to be profitable, the middle-brow tastes of American theater-goers, and the lack of copyright protection and compensation for playwrights. The primary 19th Century Theatrical Form was melodrama, despite other influences, becoming the most popular by 1840. Characteristics of Melodrama:

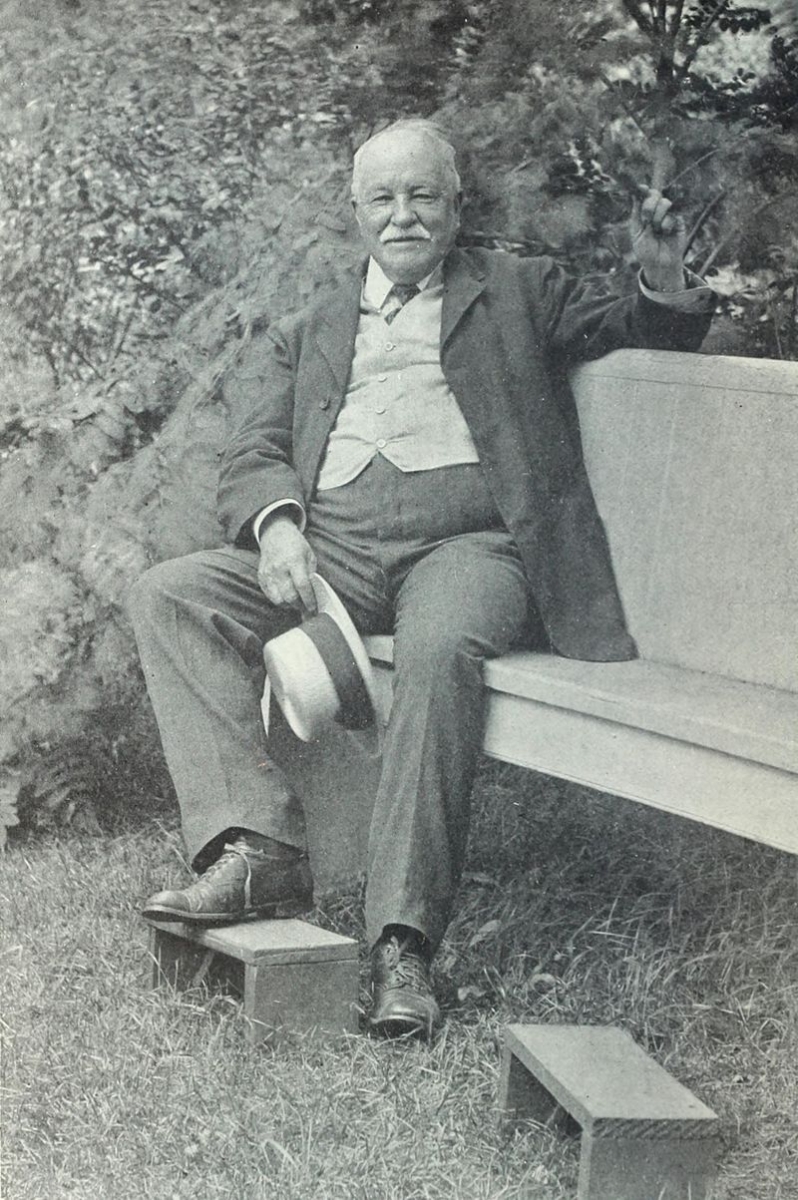

The Rise of American Realism  Many cultural currents influenced the introduction of a realistic approach to dramatizing contemporary life. One would hope that the Civil War and the assassination of a President (in a theatre no less!) was enough melodrama for a generation of Americans. The nation's growth and prosperity was spurred on by a mix of post-war progress such as the successful connection of the transatlantic telegraph cable (1866) and the first transcontinental railroad completed in United States (1869); international advances in medicine and science such as pasteurization and "The Origin of the Species"; and a continuous wave of European immigration and the rising potential for international trade. Through all mediums including painting, literature and music, American Realism attempted to portray the exhaustion and cultural exuberance of the figurative American landscape and the life of ordinary Americans at home. Artists used the feelings, textures and sounds of the city to influence the color, texture and look of their creative projects. Musicians noticed the quick and fast-paced nature. Writers and authors told a new story about Americans; boys and girls real Americans could have grown up with. Pulling away from fantasy and focusing on the now, American Realism presented a new gateway and a breakthrough - what it means to be in the present. The earliest period of American realism in drama can be dated 1870 to 1900. Elements of dramatic realism were finding their way into melodrama (e.g., Augustin Daly's "Under the Gaslight") and in local color plays (Bronson Howard's "Shenandoah" pic left). Other key dramatists during this period were David Belasco (pic right, "Girl of the Golden West"), Steele MacKaye, our man William Dean Howells, Dion Boucicault, and Clyde Fitch. Realism onstage called forth a set of dramatic and theatrical conventions with the aim of bringing a greater fidelity of real life to texts and performances:

The other novelists whose works were considered part of this 19th century movement included Stephen Crane, Horatio Algier, Henry James and, of course, William Dean Howells. Howells and Realism in Dramatic Literature  The

greatest

literary

influence

exerted on

Howells was by

the writer

whom he called

"one of the

greatest

realists who

has ever

lived" --

Carlo Goldoni

(1707-1793),

the Italian

playwright and

librettist

from the

Republic of

Venice.

His works

include some

of Italy's

most famous

and best-loved

plays.

Audiences have

admired the

plays of

Goldoni for

their

ingenious mix

of wit and

honesty. His

plays offered

his

contemporaries

images of

themselves,

often

dramatizing

the lives,

values, and

conflicts of

the emerging

middle

classes. The

greatest

literary

influence

exerted on

Howells was by

the writer

whom he called

"one of the

greatest

realists who

has ever

lived" --

Carlo Goldoni

(1707-1793),

the Italian

playwright and

librettist

from the

Republic of

Venice.

His works

include some

of Italy's

most famous

and best-loved

plays.

Audiences have

admired the

plays of

Goldoni for

their

ingenious mix

of wit and

honesty. His

plays offered

his

contemporaries

images of

themselves,

often

dramatizing

the lives,

values, and

conflicts of

the emerging

middle

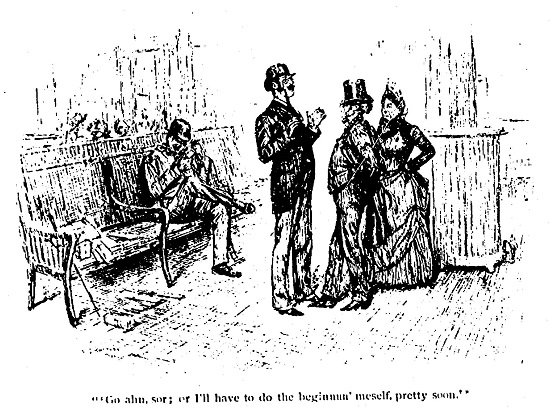

classes. There is abundant evidence that the Venetian dramatist more than any other writer, turned Howells from Romantic poet into prose Realist. It was through Goldoni's eyes that Howells, on assignment as consul to Venice from 1861-1865, first saw the possibilities of prose fiction based on the commonplace events of contemporary life. Later Goldoni's plays provided direct inspiration for his own comedies and farces. Howells, (in "My Literary Passions," 1895): "I had a notion that, in literature, persons and things should be nobler and better than they are in sordid reality; and this romantic glamour veiled the world to me, and kept me from seeing things as they are. But in the lanes and alleys of Venice I found Goldoni everywhere. Scenes from his plays were enacted before my eyes, with all the charming Southern vividness of speech and gesture, and I seemed at every turn to have stepped unawares into one of his comedies. " Howells defines Goldoni's elements of realism, as if he is talking about his own: "a) the truthful treatment b) of commonplace material, which produces c) proper moral effect," ".. there is seldom anything more poignant in any one of [Goldoni's plays] than there is in the average course of things. The plays are light and amusing transcripts from life, for the most part, and where at times they deepen into powerful situations, or express strong emotions, they do so with persons so little different from the average of our acquaintance that we do not remember just who they are." "I know none of his plays that insults the common sense with the romantic pretense that wrong will be right if you will only paint it rose-color. He is at some obvious pains to 'punish vice and reward virtue' ... no feigning that passion is a reason or justification ... nor that suffering of one kind can atone for the wrong of another." The Railroad Plays There are four plays in the Howells canon that take place in and around trains, The Parlor Car,"The Smoking Car," "The Albany Depot" (see illustration at left) and "Room Forty-Five." The designation, "The Railroad Plays" was applied by Alan Ackerman, a theater scholar, as a point of discussion for the Dramatic Realists' appropriation of common public spaces as settings for private intimate exchanges between characters. [American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 Vol. 30, No. 1 (Fall, 1997)] Ackerman notes this as a fundamental difference between late 19th century realistic drama and the romantic melodrama that came before it, the notion of a transparent "fourth wall" through which the audience unobserved can peer into the private world of the play. In general Howells' plays mock overt theatricality and focus on the ordinary and intimate experiences of the upper-middle class, experiences that are represented primarily in talk. The refinement or "culture" of the characters and the literary quality of the plays themselves are thrown into relief particularly when they are set in erstwhile public spaces such as railroads or hotels, where the principals encounter by chance less privileged characters and physical conditions. The everyday settings of his plays include a hotel, a New York apartment, a train-car: natural places where people easily meet. The incidents are those of real events rather than fictions but drawing room comedy and depend for the their effect on the subtle contract of social values. These settings and events produce scenes in which one meets probability in everything ...  The Parlor

Car,

written 1876,

was not only

the first of

the so-called

railroad plays

but was in

fact the first

of

Howells' 25

one-act

dramas.

The injection

of private

intimate

experience

into public

space became a

crucial aspect

of American

life as the

19th century

wore on,

Howells was a

primary

theorist of

this

shift.

It is,

therefore, no

mere

coincidence

that four of

Howells's

situation

comedies, a

genre to which

he devoted

considerable

energies for

thirty-five

years, are set

in railroad

cars or

depots.

The Parlor

Car,

written 1876,

was not only

the first of

the so-called

railroad plays

but was in

fact the first

of

Howells' 25

one-act

dramas.

The injection

of private

intimate

experience

into public

space became a

crucial aspect

of American

life as the

19th century

wore on,

Howells was a

primary

theorist of

this

shift.

It is,

therefore, no

mere

coincidence

that four of

Howells's

situation

comedies, a

genre to which

he devoted

considerable

energies for

thirty-five

years, are set

in railroad

cars or

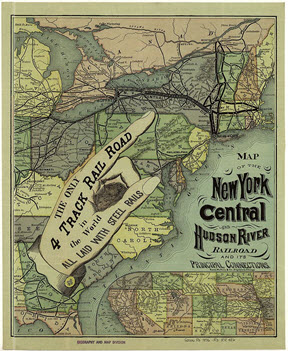

depots.This little play transforms a public space into a private situation and in doing so it is emblematic of the transformation of American theatre in the second half of the nineteenth century. The trajectory of an American theatre of rowdy spaces of audience visibility and auditability transforming to darkened auditoriums habituated by only a small cross-section of the population may be imagined for better or worse as the parlor car, disengaged from the speeding train, left quietly on the tracks. From critic Fred Lews Pattee, in "A History of American Literature": The lightness of Howells' touch, his genuine wit, and his mastery of dialogue appear at their best his little parlor comedies. Nothing as good in their line is be found in American literature. Had he written nothing he would still be remembered as the laureate of the trivial, who with exquisite prose style and sparkling humor made classics from the ordinary experiences of human life." Travelogue  William Dean Howells wrote extensively of his travels in and about European cities such as Venice and London. This quality of observation builds the world of The Parlor Car with travel schedules, railway trivia, boating on the Hudson, fashion and cigars. Trains By 1876, the year The Parlor Car was published, railroads had become America's primary mode of long distance transportation. The play is set on the New York Central Railroad which operated in the Great Lakes and Mid Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Midwest along with the intermediate cities of Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, and Syracuse. New York Central was headquartered in New York City's New York Central Building, adjacent to its largest station, Grand Central Terminal. (See map from 1876, right.) In William Dean Howell's play, the train is delayed in Rochester, picks up our romantic couple Syracuse and then strands them somewhere between Utica and Schenectady, on its way to Albany. (See Schenectady Station, left.) The railroad was established in 1853 by Albany industrialist and Railroad owner Erastus Corning, consolidating some of the oldest existing railroad companies in America including the companies referred to in the play:

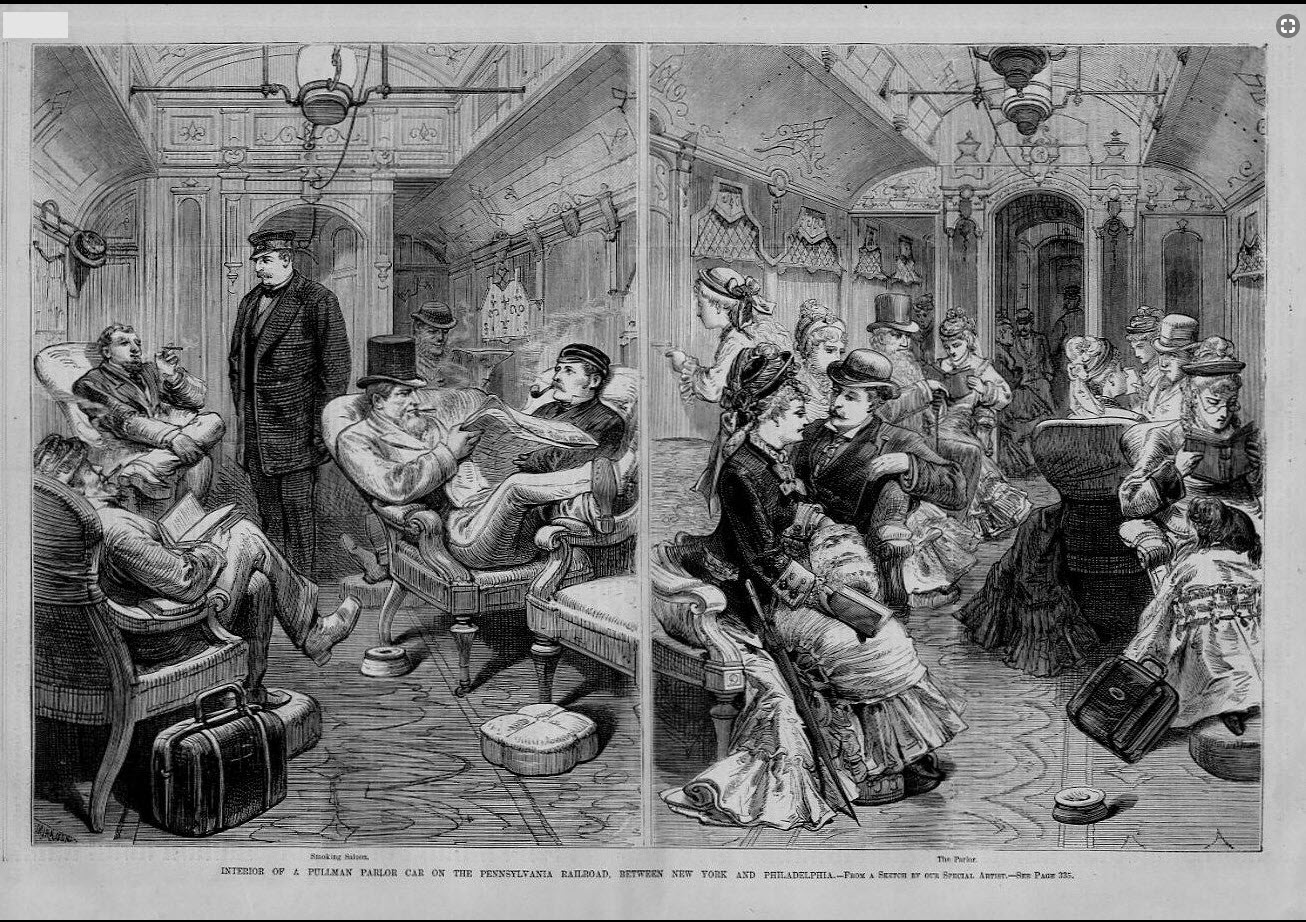

"A Pullman

parlor car

offered

respectable

and domestic

amenities to

those able to

pay for them.

The car

interior

resembles a

fine parlor in

a private

home, and no

parlor was

complete

without a

woman to

preside over

it." (From

“Railway

Passenger

Travel,”

Scribner’s

Magazine,

September 1888) "A Pullman

parlor car

offered

respectable

and domestic

amenities to

those able to

pay for them.

The car

interior

resembles a

fine parlor in

a private

home, and no

parlor was

complete

without a

woman to

preside over

it." (From

“Railway

Passenger

Travel,”

Scribner’s

Magazine,

September 1888) Parlor accommodations were appreciated by those who used

them because

of their

exclusivity.

Journalist H.

L. Mencken

(1880 - 1956,

picture left)

called the

parlor car

"the best

investment

open to an

American":

"He not only

has a certain

seat of his

own, free from

intrusion and

reasonably

roomy; he also

rides in a car

in which all

of the people

are clean and

do not smell

badly. The

stinks in a

day-coach,

even under the

best of

circumstances,

are revolting.

The imbecile

conversation

that goes on in parlor-car

smoke-rooms is

sometimes hard

to bear, but

there is

escape from it

in one's seat;

the gabble in

day-coaches is

worse, and it

is often

accompanied by all sorts of other noises." Parlor accommodations were appreciated by those who used

them because

of their

exclusivity.

Journalist H.

L. Mencken

(1880 - 1956,

picture left)

called the

parlor car

"the best

investment

open to an

American":

"He not only

has a certain

seat of his

own, free from

intrusion and

reasonably

roomy; he also

rides in a car

in which all

of the people

are clean and

do not smell

badly. The

stinks in a

day-coach,

even under the

best of

circumstances,

are revolting.

The imbecile

conversation

that goes on in parlor-car

smoke-rooms is

sometimes hard

to bear, but

there is

escape from it

in one's seat;

the gabble in

day-coaches is

worse, and it

is often

accompanied by all sorts of other noises."Wood-cut to the right engraving is titled "INTERIOR OF A PULLMAN SMOKER and PARLOR CAR ON THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD BETWEEN NEW YORK AND PHILADELPHIA", published in "Frank Leslie's Illustrated" January 1876. This dated engraving from the year of 1876.  A colorful contemporaneous view of the railroads comes from Charles Dickens (1812 - 1870), who with his wife made a first trip to the United States and Canada in 1842. They took a one-day excursion from Boston to the factories of Lowell. His recollections of the trip survive mostly in his travelogue, "American Notes for General Circulation," published later that year. Dickens noticed that the American railroads had no distinct first and second class carriages like their British counterparts. Rather, he remarked that the railroad cars were divided into gentlemen’s cars (where everyone smoked) and ladies’ cars (where no one did). He also noted, nineteenth-century perspective clearly exhibited, that “as a black man never travels with a white one, there is also a negro car”, which he went on to describe as a “great, blundering, clumsy chest”. He found the railroad cars to provide a “great deal of jolting, a great deal of noise, a great deal of wall, not much window, a locomotive engine, a shriek, and a bell”. The cars, he said were like “shabby omnibuses, but larger, holding thirty, forty, or fifty people.” For warmth, the cars were equipped with a stove, he noted, fed with charcoal or anthracite coal, which was red-hot and “insufferably close”. Through the light of its embers, one could see fumes co-mingle with the tendrils of smoke wafting in from the gentlemen’s car. Gentlemen did ride in the ladies’ car, when they accompanied ladies. Also, some ladies travelled alone. Dickens bristled at the informality exhibited by the train conductor (“or check-taker, or guard, or whatever he may be”): “He walks up and down the car, and in and out of it, as his fancy dictates; leans against the door with his hands in his pockets, and stares at you, if you chance to be a stranger; or enters into conversation with the passengers about him.” He also found it odd that “everybody” on the train “talks to you, or to anybody else who hits his fancy.” Dickens noted that politics was much discussed aboard the train, as were banks and cotton. He also noted that, as today, “that directly [after] the acrimony of the last [presidential] election is over, the acrimony of the next one begins”. George Mortimer Pullman and Luxury on the Railroad George Mortimer Pullman (1831-1897) made his name famous as the designer of the eponymous sleeping car, which made its debut in 1865. But sleeping cars had been around since the 1830s - so what made Pullman’s stand out? Comfort. The older 24-person sleeping cars left a lot to be desired and savvy designers leaped at the chance to improve long-distance train travel. George Pullman was a cabinet-maker, engineer, and building-mover.  After a particularly uncomfortable train ride, Pullman worked with the Chicago and Alton Railroad Company in 1862 to redesign and remodel their passenger coaches. The Pioneer, as he dubbed his design:

The publicity turned the Pullman sleeping car into an overnight success. And, of course, civilized travel came with a slightly steeper price tag. But in the 19th century, and even into the 20th, long-distance train travel was almost exclusively enjoyed by the wealthy and the growing middle class. And though the Pullman Sleeper required a small additional fare, a berth wasn't unreasonable for people who could afford to travel far enough to need one. As the rail network grew, so did Pullman's empire. He rapidly expanded his enterprise and by 1867, he was running nearly 50 cars on three different railroads. He also developed some new designs: a hotel car, which was basically a Manhattan apartment on wheels, a parlor car, a dining car, and perhaps most importantly, a train vestibule, which made it easy to safely move from one train car to another. Dayboat to Poughkeepsie  The two lovers met on a Dayboat to

Poughkeepsie.The

picture to the

left is the

day boat

disembarkation

in

Pougjkeepsie,

circa

1880.

Many travelers

took the Day

Line boats to

the Catskill

Mountains

region for

summer

vacations

accompanied by

family and

large trunks

of

clothes.

Others took

the boats to

riverside

parks like

Bear Mountain

State Park and

Kingston Point

Park where

they could

spend the day

picnicking and

relaxing, and

then catc h

another

steamer home

again in the

evening.

Many groups from schools, clubs, and other organizations

took yearly

outings on the

Hudson River

Day Line.

The two lovers met on a Dayboat to

Poughkeepsie.The

picture to the

left is the

day boat

disembarkation

in

Pougjkeepsie,

circa

1880.

Many travelers

took the Day

Line boats to

the Catskill

Mountains

region for

summer

vacations

accompanied by

family and

large trunks

of

clothes.

Others took

the boats to

riverside

parks like

Bear Mountain

State Park and

Kingston Point

Park where

they could

spend the day

picnicking and

relaxing, and

then catc h

another

steamer home

again in the

evening.

Many groups from schools, clubs, and other organizations

took yearly

outings on the

Hudson River

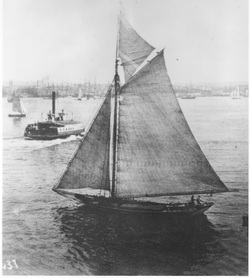

Day Line.Whatever the reason f or travel, the Hudson River Day Line provided its passengers with comfort, elegance, and some of the most beautiful scenery in the world at reasonable prices. The Hudson Highlands and West Point were known to travelers from Europe from illustrations in travel books, and a visit to New York was not complete without a trip on the Hudson to see these famous sights. A band or orchestra was always provided on board for pleasant travel, as was a fine restaurant and a cafeteria for less formal meals. Other amenities provided included writing rooms, news-stands, barber shops, and on one steamer, a darkroom for passengers to develop their own photographs en route. The term "floating palaces" aptly described the Hudson River Day Line steamers. Millions of people had happy memories of pleasant summer days on the Hudson River Day Line boats including the Chauncey Vibbard, the Daniel Drew, the Albany, the Hendrick Hudson, the Robert Fulton, the Washington Irving, the Alexander Hamilton, and the Peter Stuyvesant. Hudson River Sloops The hero of T  he Parlor Car refers to his "walking

over a slope"

at

night.

The Hudson

River sloop

was the main

means of

transportation

on the Hudson

River from the

early days of

Dutch

settlement in

the 17th

century

(1600s) until

the advent of

the steamboat

as an

affordable

alternative in

the

1820s.

Based on a

Dutch design,

this

single-masted

sailboat

carried

passengers and

cargoes up and

down the

Hudson River

between New

York and

Albany and

points in

between for

over two

hundred

years.

There were

hundreds of

these

vessels.

A trip between

New York and

Albany could

take anywhere

from 24 hours

(a very fast

trip) to

several days,

as speed was

dependent on

wind and

weather

conditions.

Passengers

prepared by

bringing food

and drink to

enhance what

was offered

on

board, and

something to

do with their

time, like

books and

sewing in case

the wind was

light.

Sometimes if

there was no

wind a sloop

would anchor,

and passengers

would go

ashore for a

picnic or a

stroll.

Note the steam

ferry and the

sloop in the

picture to the

left. he Parlor Car refers to his "walking

over a slope"

at

night.

The Hudson

River sloop

was the main

means of

transportation

on the Hudson

River from the

early days of

Dutch

settlement in

the 17th

century

(1600s) until

the advent of

the steamboat

as an

affordable

alternative in

the

1820s.

Based on a

Dutch design,

this

single-masted

sailboat

carried

passengers and

cargoes up and

down the

Hudson River

between New

York and

Albany and

points in

between for

over two

hundred

years.

There were

hundreds of

these

vessels.

A trip between

New York and

Albany could

take anywhere

from 24 hours

(a very fast

trip) to

several days,

as speed was

dependent on

wind and

weather

conditions.

Passengers

prepared by

bringing food

and drink to

enhance what

was offered

on

board, and

something to

do with their

time, like

books and

sewing in case

the wind was

light.

Sometimes if

there was no

wind a sloop

would anchor,

and passengers

would go

ashore for a

picnic or a

stroll.

Note the steam

ferry and the

sloop in the

picture to the

left.Other References Polonaise  Our heroine's interest in the "polonaise"

suggests that

she is very

much in the

thick of

popular

fashion.

The robe à la

polonaise or

polonaise is a

woman's

garment of the

later 1770s

and 1780s or a

similar

revival style

of the 1870s

inspired by

Polish

national

costume,

consisting of

a gown with a

cutaway,

draped and

swagged

overskirt,

worn over an

underskirt or

petticoat.

From the late

19th century,

the term

polonaise also

described a

fitted

overdress

which extended

into long

panels over

the

underskirt,

but was not

necessarily

draped or

swagged.

The dress

pattern to the

left is from

1873,

contemporaneous

with The

Parlor Car. Our heroine's interest in the "polonaise"

suggests that

she is very

much in the

thick of

popular

fashion.

The robe à la

polonaise or

polonaise is a

woman's

garment of the

later 1770s

and 1780s or a

similar

revival style

of the 1870s

inspired by

Polish

national

costume,

consisting of

a gown with a

cutaway,

draped and

swagged

overskirt,

worn over an

underskirt or

petticoat.

From the late

19th century,

the term

polonaise also

described a

fitted

overdress

which extended

into long

panels over

the

underskirt,

but was not

necessarily

draped or

swagged.

The dress

pattern to the

left is from

1873,

contemporaneous

with The

Parlor Car.

Embroidered Cigar Cases  Cigars and their accoutrement were very much

a part of 19th

century life.

By the middle

of the

nineteenth

century,

smoking cigars

had become so

universal as

to require: Cigars and their accoutrement were very much

a part of 19th

century life.

By the middle

of the

nineteenth

century,

smoking cigars

had become so

universal as

to require:The cigar became a status symbol in the United States, in part, because of its use by such well-respected figures as President Ulysses S. Grant and the writer Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens, a good friend of William Dean Howells). Twain expressed his love of tobacco and cigars often in speeches and in his non-fiction. In his Following the Equator (1897), the author writes "I pledged myself to smoke but one cigar a day. I kept the cigar waiting until bedtime, then I had a luxurious time with it. But desire persecuted me every day and all day long; so, within the week I found myself hunting for larger cigars than I had been used to smoke; then larger ones still, and still larger ones." The famous Henry Clay cigar, named after the American senator, was launched toward the end of the nineteenth century as a premium cigar product. By the end of the nineteenth century there were more than 7,000 cigar factories in the United States, with some 500 located in the state of Florida. The Parlor Car, First Publication  Augustin

Daly (1838 –

1899) Augustin

Daly (1838 –

1899)It starts with John Augustin Daly, playwright and for three decades one of America's foremost theatrical producers and managers. Among other contributions, Daly encouraged  American

playwrights by

producing

their plays

and calling in

print and

correspondence

for even

better plays.

He also

encouraged

contemporary

literary

figures such

as Bret Harte,

Mark Twain,

William Dean

Howells, and

Henry James to

write plays

for

production.

When his

company took

over the Fifth

Avenue

Theatre, in

1874, Daly

sent a request

to Samuel

Clemens for a

new play Daly

might produce.

Clemens

declined: American

playwrights by

producing

their plays

and calling in

print and

correspondence

for even

better plays.

He also

encouraged

contemporary

literary

figures such

as Bret Harte,

Mark Twain,

William Dean

Howells, and

Henry James to

write plays

for

production.

When his

company took

over the Fifth

Avenue

Theatre, in

1874, Daly

sent a request

to Samuel

Clemens for a

new play Daly

might produce.

Clemens

declined: Samuel Clemens (1835 - 1910) My dear Mr. Daly, Oct. 29. Although I am not able to write a play now, there are better men that can. Would it not be well worth your while to provoke W. D. Howells of the Atlantic Monthly into writing a play? My reason for making the suggestion is that I think he is writing a play. I by no means know this, but I guess it from a remark dropped by an acquaintance of his. I know Howells well, but he has not confided anything of the kind to me. Still, I think if you and Bronson are done with your fight (I mean the newspaper one) it would be a right good thing to hurl another candidate into the jaws of the critics. I am not meaning to intrude & hope I am not. Yrs. truly, Sam L. Clemens Mr. Daly did venture in accordance with Mark Twain's (see picture of Howells and Clemens) suggestion gently to "provoke" Mr. Howells into writing a play, and received the following : Cambridge, Mass. Nov. 14, 1874. My dear Sir: — Do not suppose from the great  deliberation

with which I

answer your

obliging

letter that I

was not very

glad indeed to

get it. I have

long had the

notion of a

play, which I

have now

briefly

exposed to Mr.

Clemens, and

which he

thinks will

do. It's

against it, I

suppose, that

it's rather

tragical, but

perhaps —

certainly if

you've ever

troubled

yourself with

my undramatic

writings, —

you know that

I can't deal

exclusively in

tragedy, and I

think I could

make my play

in some parts

such a light

affair that

many people

would never

know how

deeply they

ought to have

been moved by

it.

deliberation

with which I

answer your

obliging

letter that I

was not very

glad indeed to

get it. I have

long had the

notion of a

play, which I

have now

briefly

exposed to Mr.

Clemens, and

which he

thinks will

do. It's

against it, I

suppose, that

it's rather

tragical, but

perhaps —

certainly if

you've ever

troubled

yourself with

my undramatic

writings, —

you know that

I can't deal

exclusively in

tragedy, and I

think I could

make my play

in some parts

such a light

affair that

many people

would never

know how

deeply they

ought to have

been moved by

it. I have also the idea of a farce or vaudeville of strictly American circumstances. Of course I'm a very busy man, and I must do these plays in moments of leisure from my editorial work. I'm well aware that I can't write a good play by inspiration, and when I've sketched my plots and done some scenes I shall, with your leave, send them for your criticism. Yours very truly, W. D. Howells.  The

requirements

of the past

season had

prevented

Augustin from

staging Mr. W.

D. Howells'

first play,

which had been

announced for

as early as

August, 1876

(for the Fifth

Avenue, see

picture left): The

requirements

of the past

season had

prevented

Augustin from

staging Mr. W.

D. Howells'

first play,

which had been

announced for

as early as

August, 1876

(for the Fifth

Avenue, see

picture left):"A new comedietta, The Parlor Car, which has been accepted by Mr. Daly, is to be published in The Atlantic Monthly, the author preferring to have the piece criticised in advance." It will be recalled that it was at Mark Twain's suggestion that Mr. Daly proposed to the editor of The Atlantic Monthly an excursion into the dramatic field, with the result now told in these letters : "Editorial office of The Atlantic Monthly, The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass. April 24, 1876  My dear

Sir: You have

doubtless

forgotten a

very kind

invitation you

gave me

something more

than a year

since to send

you anything I

might write in

the way of a

play ; and

it's with no

purpose of

trying to

create a sense

of obligation

in you that I

recall a fact

so gratifying

to myself. My dear

Sir: You have

doubtless

forgotten a

very kind

invitation you

gave me

something more

than a year

since to send

you anything I

might write in

the way of a

play ; and

it's with no

purpose of

trying to

create a sense

of obligation

in you that I

recall a fact

so gratifying

to myself. Here is a little comedy which I have pleased myself in writing. It was meant to be printed in The Atlantic, (and so the stage direction, for the reader's intelligence, was made very full) ; but I read it to an actor the other day, and he said it would play; I myself had fancied that a drawing-room car on the stage would be a pretty novelty, and that some amusing effects could be produced by an imitation of the motion of a train, and the collision. However, here is the thing. I feel so diffident about it, that I have scarcely the courage to ask you to read it. But if you will do so, I shall be very glad. If by any chance it should please you, and you should feel like bringing it out on some off-night when nobody will be there, pray tell me whether it will hurt or help it, for your purpose, to be published in The Atlantic. Yours trulv W. D. Howells. Mr. Howells received comments from Mr. Daly and sends rewrites and suggests that Mr. Daly may be less than enthusiastic as regards the prospect of the performance of the piece at his Fifth Avenue Theatre. (See poster to the left.) Editorial office of The Atlantic Monthly. The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass. May 9, 1876. My dear Mr. Daly: I am very much gratified that you like my little farce, though your kindness makes me feel its slightness all the more keenly. If you think it will play, it is at your disposal; I could not imagine a better fortune for it than you suggest ; and if it fails, I shall have the satisfaction — melancholy but entirely definite — of knowing that it was my fault. I suppose that even if my Parlor Car meets with an accident it need not telescope any future dramatic attempt of mine ? I confide in your judgment and experience; and I am going to send you some half dozen pa  ges more

of this size,

supplying some

further shades

of character

in the lady's

case, and

heightening

the effect of

the

catastrophe.

Very truly

yours , W. D.

Howells. ges more

of this size,

supplying some

further shades

of character

in the lady's

case, and

heightening

the effect of

the

catastrophe.

Very truly

yours , W. D.

Howells. A clipping from the Boston Globe, July 24, 1876, announcing the delay of the production and the upcoming publication in the Altlantic Monthly.  While

The Parlor

Car was

waiting to be

attached to

the first

available

train, the

author was

employing his

spare hours in

a dramatic

work of more

dignity : a

comedy in four

acts which was

also to be

submitted to

the manager of

the Fifth

Avenue

Theatre. (See

poster to the

left.)

It was

completed in

due time and

read, but, not

at all to the

author's

disappointment

(for he said

he had little

hopes of its

"theatricability"),

it was found

wanting. While

The Parlor

Car was

waiting to be

attached to

the first

available

train, the

author was

employing his

spare hours in

a dramatic

work of more

dignity : a

comedy in four

acts which was

also to be

submitted to

the manager of

the Fifth

Avenue

Theatre. (See

poster to the

left.)

It was

completed in

due time and

read, but, not

at all to the

author's

disappointment

(for he said

he had little

hopes of its

"theatricability"),

it was found

wanting.The Parlor Car was never produced by Augustin Daly, though it was published first in The Atlantic Monthly in 1876 and later in various collections of Howells' play and of American one-acts. |

|

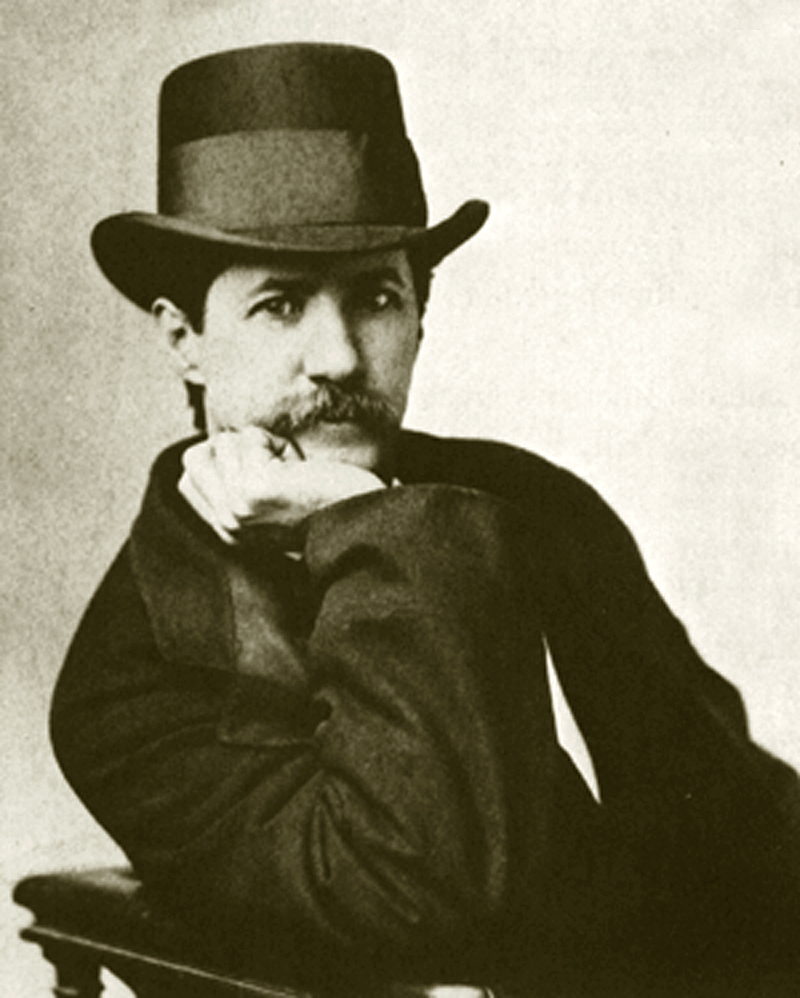

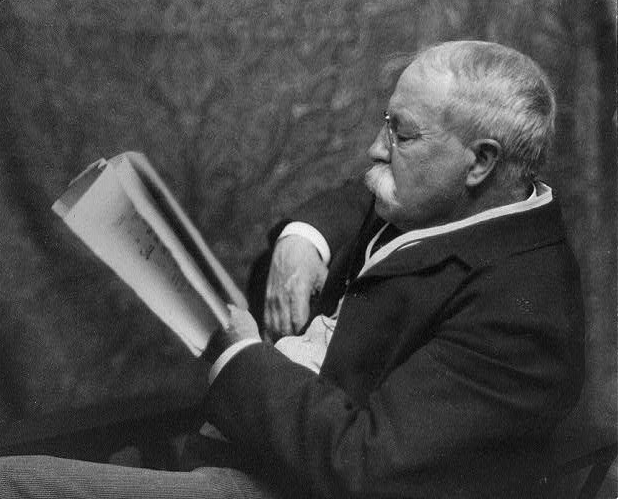

William Dean

Howells William Dean HowellsWilliam Dean Howells (1837-1920), author, editor, and critic, was born on 1 March 1837 in Martinsville, now Martins Ferry, Ohio, the second son of eight children born to Mary Dean Howells and William Cooper Howells, a printer and publisher. As the family moved from town to town, including a year-long residence at a utopian commune in Eureka Mills, later described in his New Leaf Mills (1913), Howells worked as a typesetter and a printer's apprentice, educating himself through intensive reading and the study of Spanish, French, Latin, and German. After a term as city editor of the Ohio State Journal in 1858, Howells published poems, stories, and reviews in the Atlantic Monthly and other magazines. A longer work, his campaign biography for Abraham Lincoln, earned him enough money to travel to New England and meet the great literary figures of the day-Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, James Russell Lowell, and Walt Whitman among them. Awarded the post of U. S. Consul to Venice in 1861 for his service to the Lincoln campaign, Howells lived in Italy for nearly four years. During his residence there, he married Elinor Mead Howells in 1862, and by 1872 the couple had three children: Winifred (b. 1863), John Mead (b. 1868), and Mildred (b. 1872). After leaving Venice, Howells became first the assistant editor (1866-71) and then the editor (1871-1881) of the Atlantic Monthly, a post that gave him enormous influence as an arbiter of American taste. Publishing work by authors such as Mark Twain and Henry James, both of whom would become personal friends, Howells became a proponent of American realism, and his defense of Henry James in an article for The Century (1882) provoked what was called the "Realism War," with writers on both sides of the Atlantic ocean debating the merits of realistic and romantic fiction. While writing the "Editor's Study" (1886-1892) and "Editor's Easy Chair" (1899-1909) for Harper's New Monthly Magazine and occasional pieces for The North American Review, Howells championed the work of many writers, including Emily Dickinson, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Hamlin Garland, Sarah Orne Jewett, Charles W. C  hesnutt,

Frank Norris, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Abraham Cahan, and

Stephen Crane. He was also responsible for promoting

such European authors as Ibsen, Zola, Pérez Galdós,

Verga, and Tolstoy. Despite Howells's professional

success, his personal life during this period was marred

in 1889 by the premature death of his daughter Winifred,

whose physical symptoms were misdiagnosed as resulting

from a nervous disorder and were ineffectively treated. hesnutt,

Frank Norris, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Abraham Cahan, and

Stephen Crane. He was also responsible for promoting

such European authors as Ibsen, Zola, Pérez Galdós,

Verga, and Tolstoy. Despite Howells's professional

success, his personal life during this period was marred

in 1889 by the premature death of his daughter Winifred,

whose physical symptoms were misdiagnosed as resulting

from a nervous disorder and were ineffectively treated.

After the execution of the Haymarket radicals in 1887, which he risked his reputation to protest, Howells became increasingly concerned with social issues, as seen in stories such as "Editha" (1905) and novels concerned with race (An Imperative Duty, 1892), the problems of labor (Annie Kilburn, 1888), and professions for women (The Coast of Bohemia, 1893). Although he wrote over a hundred books in various genres, including novels, poems, literary criticism, plays, memoirs, and travel narratives, Howells is best known today for his realistic fiction, including A Modern Instance (1881), on the then-new topic of the social consequences of divorce; The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885), his best-known work and one of the first novels to study the American businessman; and A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890), an exploration of cosmopolitan life in New York City as seen through the eyes of Basil and Isabel March, the protagonists of Their Wedding Journey (1871) and other works. Other important novels include Dr. Breen's Practice, (1880), The Minister's Charge and Indian Summer (1886), April Hopes (1887), The Landlord at Lion's Head (1897), and The Son of Royal Langbrith (1904). |

|

|

|

|